The construction of fortifications began upon the arrival of Union troops on May 5, 1864.

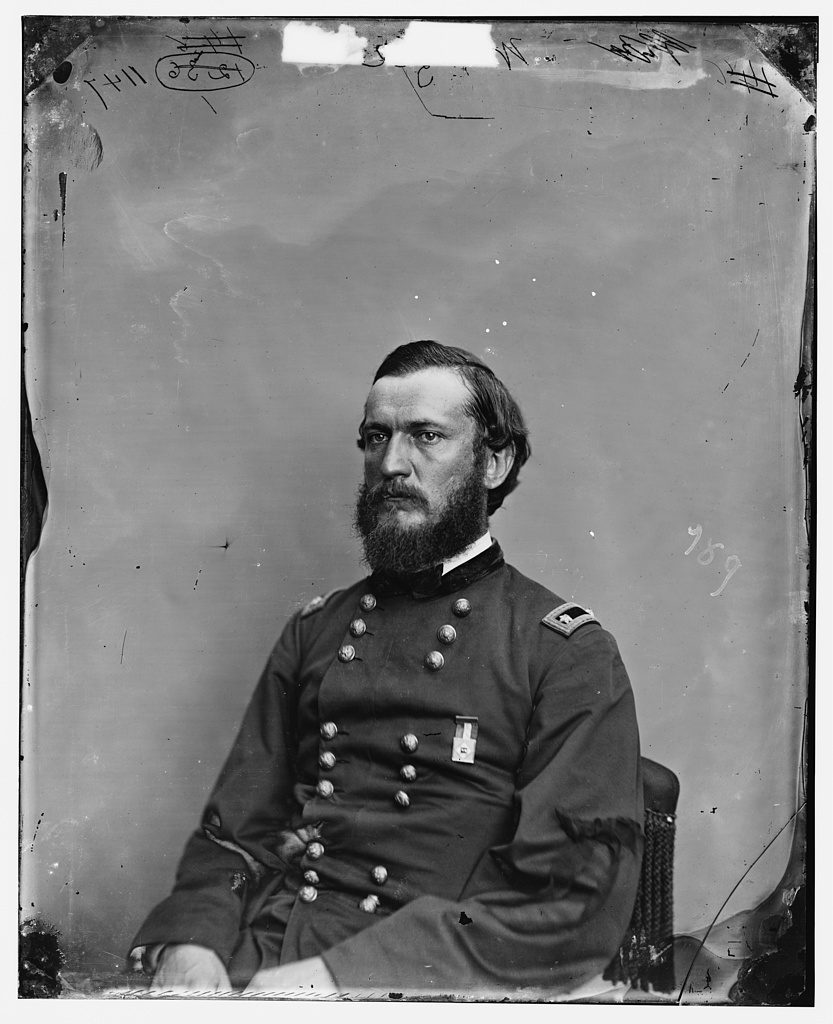

The earthworks were certified by Brigadier General Godfrey Weitzel, who was serving as Chief Engineer to Major General Butler in 1864. Weitzel would be promoted to Major General in August of that year. The ditch and parapet structure were commonly used and known as “field fortifications.” Their purpose was to increase the defensive endurance of a force holding a location. Far from being a simple ditch and mound, the components of the parapet were mathematically calculated to maximize the defensive characteristics of the fort. The outlines of field fortifications constructed during the Civil War varied widely based upon specific terrain, number of troops and artillery pieces, and proximity to other forts.

The earthworks were certified by Brigadier General Godfrey Weitzel, who was serving as Chief Engineer to Major General Butler in 1864. Weitzel would be promoted to Major General in August of that year. The ditch and parapet structure were commonly used and known as “field fortifications.” Their purpose was to increase the defensive endurance of a force holding a location. Far from being a simple ditch and mound, the components of the parapet were mathematically calculated to maximize the defensive characteristics of the fort. The outlines of field fortifications constructed during the Civil War varied widely based upon specific terrain, number of troops and artillery pieces, and proximity to other forts.

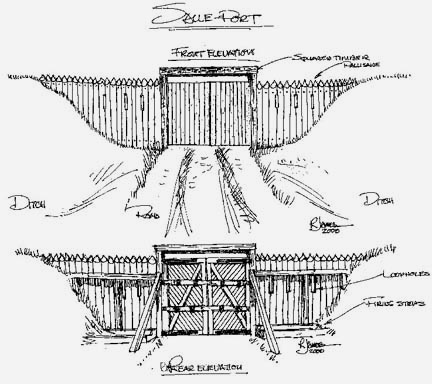

Bastions constructed at the west and east corners of the fort allowed defensive fire in several directions. This is the most probable location of the 12-15 cannons garrisoned within  the fort. Lying outside the earthworks were abatis constructed from felled trees and sharpened branches designed to slow the momentum and order of an enemy charge, causing enough delay for the defenders’ fire to be most effective. The land entrance to the fort, known as the “salle port,” would have been secured and controlled with a gated stockade constructed in typical fashion for the time. Logs 10-18 inches in diameter would have been flattened on 2 sides, placed upright in a line, sharpened at the top and buried about 4 feet into the ground. Smaller logs may have reinforced the joints. Embrasures (also called “Loopholes”) were strategically cut into the wall so men could stand upon firing steps and shoot from within the stockade.

the fort. Lying outside the earthworks were abatis constructed from felled trees and sharpened branches designed to slow the momentum and order of an enemy charge, causing enough delay for the defenders’ fire to be most effective. The land entrance to the fort, known as the “salle port,” would have been secured and controlled with a gated stockade constructed in typical fashion for the time. Logs 10-18 inches in diameter would have been flattened on 2 sides, placed upright in a line, sharpened at the top and buried about 4 feet into the ground. Smaller logs may have reinforced the joints. Embrasures (also called “Loopholes”) were strategically cut into the wall so men could stand upon firing steps and shoot from within the stockade.

Photo by Sandy Goss

Within the fort, existing buildings of the Wilson farm (est. 1835) were used for headquarters. Personal accounts describe Dr. Wilson’s house and office being used for lodging, while a barn was repurposed as a hospital. The dig undertaken by the College of William and Mary uncovered a brick foundation with a brick paved cellar; remnants of the 18th century plantation house built when the land was owned by the Kennon family. That house burned down after the war in 1876. Minie balls and a percussions cap excavated from the cellar fill give strong evidence of the home’s use during the Federal occupation. The second structure excavated consisted of a cellar with stairs cut into the subsoil, a buttress, and a long trench. Artifacts removed from this structure include a U.S. belt buckle and several Federal uniform buttons.

Within the fort, existing buildings of the Wilson farm (est. 1835) were used for headquarters. Personal accounts describe Dr. Wilson’s house and office being used for lodging, while a barn was repurposed as a hospital. The dig undertaken by the College of William and Mary uncovered a brick foundation with a brick paved cellar; remnants of the 18th century plantation house built when the land was owned by the Kennon family. That house burned down after the war in 1876. Minie balls and a percussions cap excavated from the cellar fill give strong evidence of the home’s use during the Federal occupation. The second structure excavated consisted of a cellar with stairs cut into the subsoil, a buttress, and a long trench. Artifacts removed from this structure include a U.S. belt buckle and several Federal uniform buttons.

Documented evidence proves the incomplete status of the fortifications when the Confederate attack ensued on May 24. Fitzhugh Lee’s very decision to attack the Eastern side of the fort (which today has the most imposing earthworks) supports this was considered a weak spot. The first mention of the fort being finished was in a letter written June 23, 1864 by Captain A. R. Arter. Its completion is set as a marker of the transition from the first active stage of occupancy to the second more relaxed phase when Wild’s Brigade was reassigned.